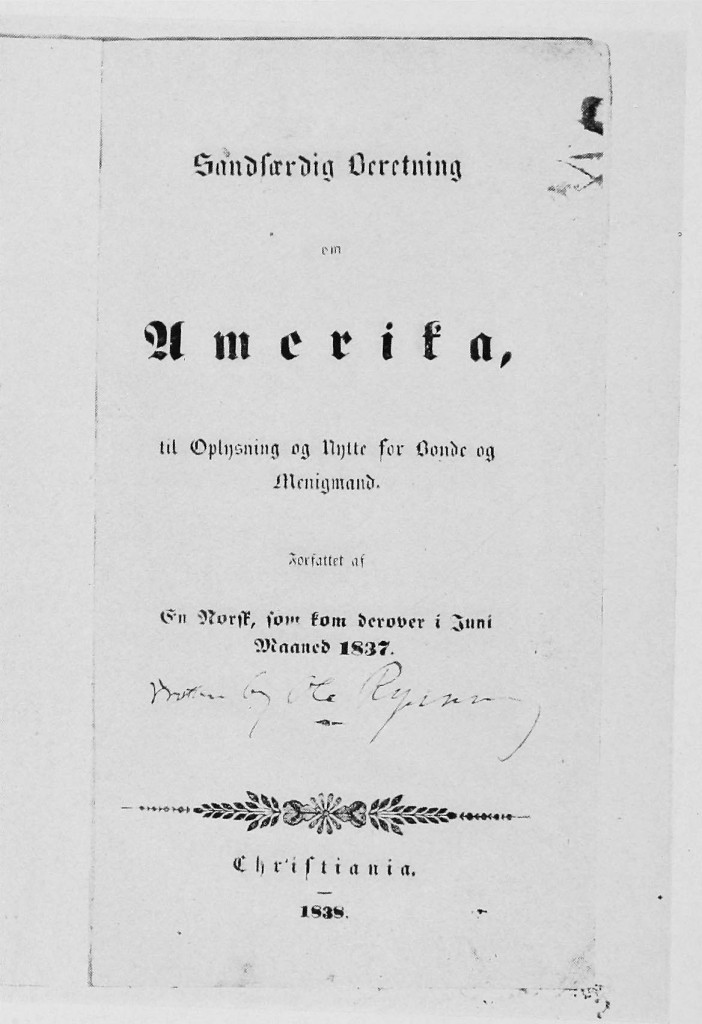

Based upon his travels in America in June of 1838, Ole Rynning’s True Account of America (Sandfærdig Beretning om Amerika) gave practical information and courage to thousands of Norwegian peasants who were curious about their chances in another country. It was the first comprehensive account of its type, having been preceded by letters sent to Norway by the relatively few earlier emigrants; these letters would be circulated around the farm communities eager for news. Rynning presented his account not as a travelogue, but explicitly as a helpful question-and-answer dialog to address the fears of the prospective emigrant. He has been accused of being overly optimistic, to his own financial advantage. Yet the fact remains that this text was enormously important in inspiring some of those in the first wave of immigrants to Illinois and Wisconsin.

Based upon his travels in America in June of 1838, Ole Rynning’s True Account of America (Sandfærdig Beretning om Amerika) gave practical information and courage to thousands of Norwegian peasants who were curious about their chances in another country. It was the first comprehensive account of its type, having been preceded by letters sent to Norway by the relatively few earlier emigrants; these letters would be circulated around the farm communities eager for news. Rynning presented his account not as a travelogue, but explicitly as a helpful question-and-answer dialog to address the fears of the prospective emigrant. He has been accused of being overly optimistic, to his own financial advantage. Yet the fact remains that this text was enormously important in inspiring some of those in the first wave of immigrants to Illinois and Wisconsin.

Below is the full text of Theodore C. Blegen’s translation of Rynning’s work [PDF], preceded by Blegen’s rather long introduction to Rynning and his book. Blegen’s translation was published in the Minnesota Historical Society’s Minnesota History in 1917 and it is free from copyright restrictions.

Blegen frequently compares Rynning’s work to Ole Nattestad’s Beskrivelse over en Reise til Nordamerika i 1837 (translated by Rasmus B. Anderson). If you’re pretty good with reading old Norwegian, also see Johannes W. C. Dietrichson’s Reise blandt de norske emigranter i “De forende nordamerikanske fristater”, 1846.

Introduction1

An intensive study of the separate immigrant groups which have streamed into America is of deep significance for an adequate understanding of our national life no less from the sociological than from the historical point of view. In tracing the expansion of population through the Mississippi Valley to the American West, the student must give careful consideration to the part played by immigrants from the Scandinavian countries. Interest in the history of the immigration of this group and in its contributions to American life has taken various forms. The most important of these are efforts in the direction of intensive research and the collection and publication of the materials essential to such research. Source material abounds; yet, owing to the fact that men whose lives have spanned almost the entire period of the main movement of Norwegian immigration are still living, no clear-cut line can be traced between primary and secondary materials. Furthermore, the comparatively recent date of Scandinavian immigration to the United States has resulted in delaying the work of collecting materials relating to the movement. Recently, however, through the work of Flora, Babcock, Evjen, Anderson, Nelson, Norelius, Holand, and others, considerable progress has been made.2 Editors of newspapers and magazines have proved assiduous in collecting and publishing accounts of pioneers; and an earnest effort to centralize all available Scandinavian materials has been inaugurated by the Minnesota Historical Society.3

The bulk of the Norwegian immigration to this country arrived after 1825. Before that time immigration from Norway was isolated, although it was not inconsiderable even in the seventeenth century.4 A preliminary trip of investigation was made in 1821 by Kleng Peerson in company with Knud Olson Eide. After three years of experience in America Peerson returned to Norway. Shortly after his arrival the sloop “Restaurationen,” with fifty-two persons aboard, sailed from Stavanger, July 4, 1825, thereby beginning the great wave of Norwegian immigration to America. The party settled in Orleans County, New York, where in the next eight or nine years a number of new immigrants from Norway joined them. In 1833 Peerson proceeded to the West in search of a site for a new settlement and, after considerable investigation, selected a section of La Salle County, Illinois. His action led to the migration of many of those who had first settled in New York and resulted in the Fox River settlement. Influenced by the letters of Gjert G. Hovland and the return of Knud A. Slogvig, approximately two hundred immigrants took passage on the “Norden” and “Den Norske Klippe” from Stavanger in July, 1836, and went directly to Illinois. In 1837 the “Enigheden” and the “Ægir” sailed with about an equal number of passengers.5 From then on Norwegian immigration increased rapidly.6

The “Ægir” was under the command of Captain Behrens, who had made a voyage to America with freight and returned to Bergen in 1836. While in the harbor of New York he had evidently examined some emigrant ships—German and English— and had informed himself as to proper accommodations for emigrants and also as to American immigration laws. Likewise from two German ministers returning to Germany aboard the “Ægir” he gained some knowledge of the German immigration to Pennsylvania. Upon his arrival at Bergen he learned that a considerable number of Norwegians were planning to emigrate, some of them having already sold their farms preparatory to departure. Perceiving his opportunity, the captain decided to remodel his ship for passenger service, and a contract was drawn up by the terms of which he was to take the party to America in the spring of 1837. Ole Rynning, who was destined to be the leader of this party, and who later, through the publication of his Sandfærdig Beretning om Amerika, became one of the important figures in the history of Norwegian immigration, joined the party at Bergen after the agreement with Captain Behrens had been made and the arrangements on board had been completed. He had read a notice of the proposed voyage in a newspaper, and had been in correspondence with the owner of the boat.7

Ole Rynning was born April 4, 1809, in Ringsaker, Norway, the son of Rev. Jens Rynning and his wife, Severine Cathrine Steen. The father was at that time curate in Ringsaker; in 1825 he became minister of the parish of Snaasen, where he remained until his death in 1857, being pastor emeritus in his later years. Ole’s parents desired him to enter the church, and in 1829 he passed the examinations for matriculation at the University of Christiania. Four years later, upon completing his work at the university, he gave up the thought of entering the ministry and returned to Snaasen, where he conducted a private school for advanced students. Langeland declares that the immediate cause of Rynning’s emigration was a betrothal which his father looked upon as a mésalliance. It seems, furthermore, that his father was of an aristocratic bent of mind, and serious differences in views existed between him and his son, who was thoroughly democratic and sympathized with the peasantry. According to the statement of his nephew, Ole had made a contract to buy a marsh with two small adjoining farms for the sum of four hundred dollars (Norwegian money). As he was unable to raise this amount he decided to seek his fortune in the new world.8 It is probable that Rynning’s case is typical of many in that his decision to emigrate was occasioned by a number of widely different, reenforcing motives.

The “Ægir” with its eighty-four passengers sailed from Bergen on April 7, 1837. In mid-ocean the vessel had a slight collision with the British ship, “Barelto,” but though the passengers were frightened, no great damage was done; and the boat arrived at New York on the evening of June 9.9 Langeland relates some interesting details regarding the voyage.

Not all Norwegians are sailors, popular ideas to the contrary notwithstanding. In this company were peasants who had never seen the sea before; they soon overcame their fear, however. During the first part of the voyage they amused themselves with peasant dances on the deck to the music of a fiddle; but the captain had to put a stop to this as it was too hard on the deck floor. A festival held on board ship is of interest because a poem composed by Rynning was sung on the occasion. His book and this verse are the only known writings from Rynning’s hand. It is the oldest piece of poetry written by a Norwegian immigrant in the nineteenth century. In somewhat free translation it may be rendered as follows:

Beyond the surge of the vast salt waves

Deep hid lies Norway’s rocky shore.

But longing yearns the sea to brave

For dim oak forests known of yore.

The whistling spruce and glacier’s boom

Are harmonies to Norway’s son.

Though destiny, as Leif and Bjorn,

Call northern son to alien West,

Yet will his heart in mem’ry turn

To native mountains loved the best,

As longs the heart of a lone son

To his loved home once more to come.10

Influenced by Slogvig and by letters from the Illinois country, the “Ægir ” party intended originally to go the settlement in La Salle County. At New York they took a steamer on the Hudson River to Albany, then went by canal boat from Albany to Buffalo, and from there continued their journey by way of Lake Erie to Detroit.11 The traveling expenses were greater than they had expected, and one of their number, Nils P. Langeland, having a large family and funds insufficient for continuing the journey, remained at Detroit.12 Here two interesting and important pioneers of the Norwegian immigration movement joined the group of immigrants. These were the brothers, Ole and Ansten Nattestad, who had reached New York by way of Gothenburg and Fall River, Massachusetts, a few days after the arrival of the “Ægir.” In his journal Ole Nattestad gives the following account of the meeting: “On the street I met one of the Norwegians who had sailed from Bergen on the seventh of April preceding. In the course of my conversation with him he said that there were about eighty persons of them, who were going to Chicago, and they had remained here five days without securing passage, but they were to leave in two days.”13 The upshot of the meeting was that the Nattestads joined the party.

The boat to Chicago was greatly crowded, and the immigrants suffered not a little inconvenience. Shortly after landing, they received from Norwegians reports unfavorable to the Fox River region, in which it had been their intention to settle. Many were discouraged, especially the women, and plans were changed. The suggestion of Beaver Creek, about seventy miles south of Chicago in Iroquois County, Illinois, as a site for settlement seems to have come from a couple of Americans, possibly land speculators, with whom Rynning talked in Chicago. Rynning at this time was particularly useful because he was able to speak English. Disappointed once, the company decided to proceed cautiously, and therefore delegated four men, whose expenses were to be paid by the party, to act as a committee of investigation. These men, Ole Rynning, Ingebrigt Brudvig, Ole Nattestad, and Niels Veste, walked south of Chicago and, after examining the land under consideration, chose a site at Beaver Creek. Ole Nattestad declared later that he did not approve of the site selected because it was too sandy and swampy. Leaving two of the committee at Beaver Creek to build a log house preparatory to the arrival of the immigrants, Rynning and Brudvig returned to Chicago to acquaint the party with the results of their investigation and to pilot it to the place of settlement.

The land at Beaver Creek was favorably described by Rynning and his companion. Accordingly, oxen and wagons were purchased, and preparations made to leave Chicago. The company was now reduced in numbers to about fifty, some having gone to Fox River with Bjorn A. Kvelve, and others having dropped out at Rochester. The remainder made their way to Beaver Creek and began at once to prepare for the oncoming winter. Land was selected, and log houses were built in sufficient number to accommodate all.

No other settlers lived in the vicinity, and there was some dissatisfaction because of difficulty in securing supplies. Langeland states that the nearest mill was seventy miles away. For a time considerable grumbling was directed against Rynning and others who were responsible for the location of the site; but when Ole Nattestad returned in the autumn from a short trip he found the colonists in good spirits. Later events proved, however, that a tragic mistake had been made. The ground, which was very low, had been examined in late summer, and, because of the dryness and the overgrowth of grass, the men had been deceived. As soon as spring came and the flat land of the settlement was under water, its truly swampy character was revealed; and the unfortunate settlers were in sore straits. To make matters worse, the climate was extremely unhealthful, and malarial fever developed among the settlers. Sickness began to claim daily victims, and most of the settlers succumbed, including Ole Rynning. Some of the survivors removed to La Salle County in the spring of the following year, but a few remained. The last to leave was Mons Aadland. In 1840, finding his capital reduced to three dollars, he exchanged his farm for a small herd of cattle and went to Racine County, Wisconsin. In realizing something for his land he was more fortunate than most of his companions. They practically fled from the settlement, and of course could not sell their land. No one cared to buy land in a swampy, malaria- infested region. “Only the empty log houses remained, like silent witnesses to the terrors of the scourge, and afforded a dismal sight to the lonesome wanderer who ventured within these domains.”14

Rynning’s personality left a deep impress upon the minds of those who knew him, and there are not a few testimonies to the inherent nobility and self-sacrificing nature of the man.- One of the survivors of the settlement, Ansten Nattestad, is reported to have said of him: “He himself was contented with little, and was remarkably patient under the greatest sufferings. I well remember one time when he came home from a long exploring expedition. Frost had set in during his absence. The ice on the swamps and the crusts of snow cut his boots. He finally reached the colony, but his feet were frozen and lacerated. They presented a terrible sight, and we all thought he would be a cripple for life.” In this condition Rynning wrote the manuscript of Sandfærdig Beretning om Amerika in the winter of 1837-38. As soon as he completed a chapter of it, he would read it aloud to Nattestad and others, to get their opinions. There is something admirable in the picture of Rynning, sick and confined to his bed, writing a description of the conditions and problems of life in the new world for the benefit of those in the old country who were considering seeking homes within its bounds. When he had regained his health, Rynning resumed work among the colonists. But in the fall of 1838 he “was again confined to the sick-bed,” according to Nattestad, “and died soon thereafter to the great sorrow of all.”15 A pathetic incident is related which illustrates the deplorable conditions in the settlement at the time of Rynning’s death. Only one person in the colony was well at the time. This man is said to have gone “out on the prairie and chopped down an oak and made a sort of coffin of it. His brother helped him to get the dead body into the coffin and then they hauled it out on the prairie and buried it.”16 Thus Ole Rynning, the leader of the “Ægir” group and, through his book, one of the noteworthy figures in the history of Norwegian immigration to America, lies in an unmarked grave.

To the philanthropic and helpful spirit of Rynning there are many testimonies. When the immigrants in Chicago received adverse reports of the Fox River region, they became completely dispirited. They had come from afar; they had ventured much; this region had been their goal; little wonder that their courage was shaken! “But in this critical situation,” says Ole Nattestad, “the greatness of Ole Rynning’s spirit was revealed in its true light. He stood in the midst of those who were ready for mutiny; he comforted the despairing, counseled with those who were in doubt, and reproved those who were obstinate. He wavered not for an instant, and his coolness, undauntedness, and noble self-sacrifice for the welfare of others calmed the spirits of all. The storm abated, and the dissatisfaction gave place to a unanimous confidence.” Ansten Nattestad declares: “All his dealings proclaimed the philanthropist. I have never known any one with such noble principles and such a completely disinterested habit of thought. . . . A great and good idea formed the central point of all his thinking. He hoped to be able to provide the poor, oppressed Norwegian workman a happier home on this side of the sea, and to realize this wish he shunned no sacrifice, endured the greatest exertions, and was patient through misunderstandings, disappointments, and loss. . . . When sickness and suffering visited the colonists, he was always ready to comfort the sorrowing and to aid those in distress so far as it lay in his power. Nothing could shake his belief that America would become a place of refuge for the masses of people in Europe who toiled under the burdens of poverty.”17

In the spring of 1838 Ansten Nattestad made a trip to Norway to visit friends and relatives, going by way of New Orleans and Liverpool. He took with him “letters from nearly all the earlier Norwegian emigrants” whom he had met, and was thus instrumental in disseminating in Norway much information about America. He carried with him also the manuscript of his brother Ole’s Beskrivelse over en Reise til Nordamerica, published in Drammen in 1839; and the manuscript of Rynning’s Sandfærdig Beretning om Amerika, published in Christiania in 1838.18 Among the peasants of Norway very little was known at this time of America; consequently there was great eagerness to get definite information on the problems connected with emigration, especially regarding prospects in the new land. Not a little light is thrown upon the situation by the following statement of Nattestad: “I remained in Numedal throughout the winter and until the following spring. The report of my return spread like wildfire through the land, and an incredible number of people came to me to hear news from America. Many traveled as far as twenty Norwegian miles19 to talk with me. It was impossible to answer all the letters which came to me containing questions in regard to conditions on the other side of the ocean. In the spring of 1839 about one hundred persons from Numedal stood ready to go with me across the sea. Among these were many farmers and heads of families, all, except the children, able-bodied and persons in their best years. In addition to these there were some from Thelemarken and from Numedal who were unable to go with me as our ship was full. We went directly from Drammen to New York.”20 Rynning’s account, together with the presence of Ansten Nattestad and the influence of Ole Nattestad’s book, had a considerable effect upon emigration, especially from Numedal, a region in the southern part of Norway between Christiania and Hardanger. The two books, particularly Rynning’s, “in which a scholarly and graphic account of conditions and prospects in the new world were presented, were quickly spread throughout Norway,” writes Anderson, “and from this time on we may regard regular emigration from various parts of Norway as fully established, though emigrant packets do not appear to have begun to ply regularly until after 1840.”21

Nilsson, relying on information supplied him by Gullik O. Gravdal, an immigrant of 1839, says of Nattestad’s return to Norway and of the influence of Rynning’s book: “Hardly any other Norwegian publication has been purchased and read with such avidity as this Rynning’s Account of America. People traveled long distances to hear ‘news’ from the land of wonders, and many who before were scarcely able to read began in earnest to practice in the ‘America-book,’ making such progress that they were soon able to spell their way forward and acquire most of the contents. The sensation created by Ansten’s return was much the same as that which one might imagine a dead man would create, were he to return to tell of the life beyond the grave. Throughout the winter he was continually surrounded by groups who listened attentively to his stories. Since many came long distances in order to talk with him, the reports of the far west were soon spread over a large part of the country. Ministers and bailiffs, says Gullik Gravdal, tried to frighten us with terrible tales about the dreadful sea monsters, and about man-eating wild animals in the new world; but when Ansten Nattestad had said Yes and Amen to Rynning’s Account, all fears and doubts were removed.”22

The report of Rynning’s death and the pathetic end of the Beaver Creek colony probably dampened the ardor of prospective immigrants. Nilsson gives an interesting account by an eyewitness of the effect of Rynning’s book and of his death upon the people of his home town. “For a time I believed that half of the population of Snaasen had lost their senses. Nothing else was spoken of than the land which flows with milk and honey. Our minister, Ole Rynning’s father, tried to stop the fever. Even from the pulpit he urged the people to be discreet and described the hardships of the voyage and the cruelty of the American savage in most forbidding colors. This was only pouring oil upon the fire. Candidate Ole Rynning was one of those philanthropists for whom no sacrifice is too great if it can only contribute to the happiness of others. He was, in the fullest sense, a friend of the people, the spokesman of the poor and one whose mouth never knew deceit. Thus his character was judged, and his lack of practical sense and his helplessness in respect to the duties of life were overlooked. But then came the news: Ole Rynning is no more. This acted as cold water upon the blood of the people. The report of his death caused sorrow throughout the whole parish, for but few have been so commonly loved as this man. Now the desire to emigrate cooled also, and many of those who formerly had spoken most enthusiastically in favor of emigration now shuddered with fear at the thought of America’s unhealthful climate, which, in the best years of his strength and health, had bereaved them of their favorite, ‘Han Ola,’ who had not an enemy but a multitude of friends, who looked up to him as to a higher being, equipped with all those accomplishments which call forth the high esteem and trust of his fellow citizens.”23 According to Reiersen, Rynning’s death caused a temporary cessation of emigration in the years from 1839 to 1841, and not until reports were fuller did the great movement of 1843 begin. A considerable number, however, emigrated in 1839. In explaining the lull during the years 1840 and 1841, Flom suggests that the prospective emigrants, realizing the many serious difficulties connected with emigration, were simply awaiting favorable news from friends and relatives in America. The tragedy at Beaver Creek probably had some effect in creating this spirit of cautiousness. The book was nevertheless distributed in many parts of Norway where no report of the Beaver Creek colonists came; and, as Babcock says, “by its compact information and its intelligent advice, it converted many to the new movement.”24

Rynning’s Sandfærdig Beretning om Amerika, a booklet of thirty-nine pages, is now very rare. A copy which formerly belonged to Rynning’s nephew, Rev. B. J. Muus, and is now in the library of the University of Illinois is the only one known to be in existence. Using this copy, Rasmus B. Anderson published a reprint in 1896 with the title Student Ole Rynnings Amerikabog.25 The edition of the reprint was so small that it is now almost as difficult to obtain as the original. Although the work has been used by writers on Norwegian immigration, this is the first complete translation.26 In making it the translator has used a copy of the reprint in the library of the Minnesota Historical Society, with corrections at some points from the copy of the original in the library of the University of Illinois.27

THEODORE C. BLEGEN

MILWAUKEE, WISCONSIN

[Title Page]

True Account of America for the Information and Help of Peasant and Commoner. Written by a Norwegian who arrived there in the month of June, 1837. Christiania. 1838.

[Verso of Title Page]

Printed in the office of Guldberg and Dzwonkowski by P. T. Malling.

Preface

DEAR COUNTRYMEN—PEASANTS AND ARTISANS:

I have now been in America eight months, and in this time have had an opportunity to learn much in regard to which I vainly sought to procure information before I left Norway. I felt at that time how unpleasant it is for those who wish to emigrate to America to be without a trustworthy and fairly detailed account of the country. I learned also how great the ignorance of the people is, and what false and preposterous reports were believed as full truth. It has therefore been my endeavor in this little publication to answer every question that I myself raised, to make clear every point in regard to which I observed that people were in ignorance, and to refute the false reports which have come to my ears, partly before my departure from Norway and partly after my arrival here. I trust, dear reader, that you will not find any point concerning which you desired information overlooked or imperfectly treated.

OLE RYNNING

ILLINOIS, February 13, 1838

Contents

1. In what general direction from Norway is America situated, and how far is it away?

2. How did the country first become known?

3. What in general is the nature of the country, and for what reason do so many people go there, and expect to make a living?

4. Is it not to be feared that the land will soon be overpopulated? Is it true that the government is going to prohibit more people from coming?

5. In what part of the country have the Norwegians settled? What is the most convenient and cheapest way to reach them?

6. What is the nature of the land were the Norwegians have settled? What does good land cost? What are the prices of cattle and of provisions? How high are wages?

7. What kind of religion is to be found in America? Is there any kind of order or government in the land, or can every one do as he pleases?

8. What provisions are made for the education of children, and for the care of poor people?

9. What language is spoken in America? Is it difficult to learn?

10. Is there considerable danger from disease in America? Is there reason to fear wild animals and the Indians?

11. For what kind of people is it advisable to emigrate to America, and for whom is it not advisable?—Caution against unreasonable expectations.

12. What particular dangers is one likely to encounter on the ocean? Is it true that those who are brought to America are sold as slaves?

13. Guiding advice for those who wish to go to America. How they should hire a ship; how they should exchange their money; what time of the year and what route are the most convenient; what they ought to take with them.

Account of America

1. In what general direction from Norway is America situated, and how far is it away?

America is a very large continent which is situated westward from Norway. It stretches about thirteen hundred [Norwegian] miles from north to south, and consists of two chief divisions which are connected only by a narrow isthmus. That part which lies north of this isthmus is called North America, and that which is situated south of it is called South America. Each of these sections includes many countries which are just as different in name, government, and situation as Norway and England, or Norway and Spain. Therefore, when emigration to America is being considered, you must ask, “To what part of America, and to what province?” The most important country in all America with respect to population as well as to freedom and happy form of government is the “United States” in North America. Usually, therefore, this country is meant when you hear some one speak of America in an indefinite way. It is to this land your countrymen have emigrated; and it is this land which I shall now describe.

The United States is situated about southwest from Norway. To go there you must sail over an ocean which is about nine hundred Norwegian miles wide. With a favorable wind and on a ship that sails well you can cross in less than a month; but the usual time is nine weeks, sometimes a little more, sometimes less.28 As a matter of fact the wind is generally from the west, and therefore against you, when you are sailing to America. Depending upon the nature of the weather, you go sometimes north of Scotland, which is the shortest way, and sometimes through the channel between England and France.

Since America lies so far to the west, noon occurs there a little over six hours later than in Norway. The sun—as commonly expressed—passes around the earth in twenty-four hours, a phenomenon experienced every day; hence six hours is one fourth of the time required in passing around. It may therefore be concluded that from Norway to America is one fourth of the entire distance around the earth.

2. How did the country first become known?

It is clearly shown by the old sagas that the Norwegians knew of America before the black death. They called the land Vinland the Good, and found that it had low coasts, which were everywhere overgrown with woods. Nevertheless there were human beings there even at that time; but they were savage, and the Northmen had so little respect for them as to call them “Skrellings.”29 After the black death in 1350 the Norwegians forgot the way to Vinland the Good, and the credit for the discovery of America is now given to Christopher Columbus, who found the way there in 1492. He was at that time in the service of the Spanish; and the Spaniards, therefore, reaped the first benefits of this important discovery.

During the reign of Queen Elizabeth over England Englishmen for the first time sailed along the western [sic] coast of North America, and Walter Raleigh established the first English colony, which he called Virginia. Gradually several colonies were established by various nations. Some Norwegians also founded a little town in 1624, which they named Bergen, in that part of the country which is now called New Jersey.30 The English maintained predominance, however, and the country was under their jurisdiction until the fourth of July, 1776, when it separated from England and formed a free government without a king. Since that time it is almost unbelievable how rapidly the country has progressed in wealth and population.

In 1821 a person by the name of Kleng Peerson from the county of Stavanger in Norway emigrated to New York in the United States. He made a short visit back to Norway in 1824 and, through his accounts of America, awakened in many the desire to go there.31 An emigration party consisting of fifty-two persons bought a little sloop for eighteen hundred speciedaler32 and loaded it with iron to go to New York. The skipper and mate themselves took part in this little speculation. They passed through the channel and came into a little outpost on the coast of England,33 where they began to sell whiskey, which is a forbidden article of sale at that place. When they found out what danger they had thereby incurred, they had to make to sea again in greatest haste. Either on account of the ignorance of the skipper or because of head winds, they sailed as far south as the Madeira Islands.34 There they found a cask of madeira wine floating on the sea, which they hauled into the boat and from which they began to pump and drink. When the whole crew had become tipsy, the ship came drifting into the harbor like a plague ship, without command, and without raising its flag. A man on a vessel from Bremen, which was lying in port, shouted to them that they must immediately hoist their flag if they did not wish to be fired upon by the cannons of the fortress, which, indeed, were already being aimed at them. Finally one of the passengers found the flag and had it raised. After this and other dangers they at length reached New York in the summer of 1825. In all, the voyage from Stavanger to America had taken fourteen weeks, which is the longest time I know any Norwegian to have been on the way.35 Nobody, however, had died on the sea, and all were well when they landed. It created universal surprise in New York that the Norwegians had ventured over the wide sea in so small a vessel, a feat hitherto unheard of.36 Either through ignorance or misunderstanding the ship had carried more passengers than the American laws permitted, and therefore the skipper and the ship with its cargo were seized by the authorities. 37 Now I can not say with certainty whether the government voluntarily dropped the matter in consideration of the ignorance and child-like conduct of our good countrymen, or whether the Quakers had already at this time interposed for them; all I am sure of is that the skipper was released, and the ship and its cargo were returned to their owners. They lost considerably by the sale of the same, however, which did not bring them more than four hundred dollars. The skipper and the mate settled in New York. Through contributions from the Quakers the others were enabled to go farther up into the country. Two Quakers in the company established themselves in Rochester. One of these, Lars Larson by name, lives there still.38 The others bought land in Murray,39 five miles northwest of Rochester. They had to give five dollars an acre, but, since they did not have money with which to liquidate the entire amount at once, they made arrangements to pay by installments within ten years. Each one bought about forty acres. The land was thickly overgrown with woods and difficult to clear. Consequently, during the first four or five years conditions were very hard for these people. They often suffered great need, and wished themselves back in Norway; but they saw no possibility of getting there without giving up the last mite of their property, and they would not return as beggars. Well- to-do neighbors assisted them, however, and by their own industry they at last got their land in such condition that they could earn a living from it, and live better than in their old native land. As a result of their letters, more Norwegian peasants were now encouraged to try their fortunes in America; but they went only singly, and commonly took the route by way of Gothenburg, Sweden, where there is often a chance to get passage for America. One of those who went by this route, a man by the name of Gjert Gregoriussen Hovland, wrote several letters to his friends in Norway, which were copied many times and sent about to many districts in the diocese of Bergen.40 In 1835 one of the first emigrants, a young bachelor named Knud Slagvigen,41 likewise made a trip back to Norway, and many persons traveled a long way just to talk with him. Thus, America began to be more and more known to peasant and commoner in the dioceses of Bergen and Christiansand. As a result two ships sailed in 1836 with emigrants from Stavanger, and in 1837 one from. Bergen and one from Stavanger,42 in addition to many emigrants who went by way of Gothenburg or Hamburg. By far the greater number of those with whom I have talked so far find themselves well satisfied with their new native land.

3. What in general is the nature of the country, and for what reason do so many people go there, and expect to make a living?

The United States is a very large country, more than twenty times as large as all Norway. The greater part of the land is flat and arable; but, as its extent is so great, there is also a great difference with respect to the mildness of the weather and the fertility of the soil. In the most eastern and northern states the climate and soil are not better than in the southern part of Norway. In the western states, on the contrary, the soil is generally so rich that it produces every kind of grain without the use of manure; and in the southern states even sugar, rice, tobacco, cotton, and many products which require much heat, are grown.

It is a general belief among the common people in Norway that America was well populated a few years ago, and that a plague—almost like the black death—has left the country desolate of people. As a result they are of the opinion that those who emigrate to America will find cultivated farms, houses, clothes, and furniture ready for them, everything in the condition in which it was left by the former owners. This is a false supposition.* When the country was first discovered, this part of America was inhabited only by certain savage nations that lived by hunting. The old inhabitants were pressed back more and more, inasmuch as they would not accustom themselves to a regular life and to industry; but as yet the greater part of the land has not begun to be cultivated and settled by civilized peoples.

* I will not deny, however, that far back in time the United States may have been populated by another and more civilized race than the savage Indians who now are commonly regarded as the first inhabitants of the country. I have, in fact, seen old burial mounds here, which resemble the Norwegian barrows; and Americans have told me that by digging in such mounds there have been found both human bones of exceptional size, and various weapons and implements of iron, which give evidence of a higher civilization than that of the Indians. It is also significant that the Indians themselves do not know the origin of these mounds.— Rynning.

4. Is it not to be feared that the land will soon be overpopulated ? Is it true that the government is going to prohibit more people from coming?

It has been stated above that the United States in extent is more than twenty times as large as Norway, and that the greater part of the’ country is not yet under cultivation. If, in addition to this, we consider that almost every foot of land in the United States is arable, while the greater part of Norway consists of barren mountains, and that America on account of its southern situation is richer than Norway in products for human subsistence, then we can without exaggeration conclude that the United ‘States could support more than one hundred times as many people as are to be found in all Norway. Now it is no doubt a fact that hundreds of thousands of people flock there yearly from various other lands of Europe, but nevertheless there is no danger that the land will be filled up in the first fifty years. When we were in New York last summer, several thousand immigrants from England, Germany, France, and other countries arrived daily. Many thoughtful men in our company became disheartened thereby, and believed that the whole country was going to become filled at once, but they soon discovered that this fear was unwarranted. Many did, indeed, make their way into the interior with us; but they became more and more scattered, and before we reached Illinois there was not a single one of them in our company. Before my departure from Norway I heard the rumor that the government in the United States was not going to permit further immigration.43 This report is false. The American government desires just this, that industrious, active, and moral people emigrate to their land, and therefore has issued no prohibition in this respect. It is true, however, that the government is anxious to prevent immigrants, upon their arrival in this country, from becoming, through begging, a burden to the inhabitants of the seaport towns.* As a matter of fact, a large number of those who emigrate to America are poor people who, when they land, have hardly so much left as to be able to buy a meal for themselves and their families. However good the prospects for the poor laborer really are in America, yet it would be too much to expect that, on the very first day he steps upon American soil, he should get work, especially in the seaport towns, where so many thousands who are looking for employment arrive daily. His only recourse, therefore, is to beg. To prevent this, the government requires the payment of a tax from every person who lands in America with the purpose of settlement. With this tax are defrayed the expenses of several poorhouses which have been established for poor immigrants. Those who at once continue their journey farther into the country are required to pay less than those who remain in the seaport, for the former can more easily find work and support themselves. When we landed in New York, the tax there was two and one-half dollars; but there is a rumor that it is going to be raised. At some places the tax is ten dollars.44

The immigrants of different nations are not equally well received by the Americans. From Ireland there comes yearly a great rabble, who, because of their tendency to drunkenness, their fighting, and their knavery, make themselves commonly hated. A respectable Irishman hardly dares acknowledge his nationality. The Norwegians in general have thus far a good reputation for their industry, trustworthiness, and the readiness with which the more well-to-do have helped the poor through the country.

*The report seems to have been circulated in Norway that those who emigrated from Stavanger in 1836 have been forced to go about in America and beg in order to raise money enough to get back to Norway. But so far as I have inquired and heard, this is purely a falsehood. I have talked with most of those who came over in 1836, and all seem to have been more or less successful.—Rynning.

5. In what part of the country have the Norwegians settled? What is the most convenient and cheapest way to reach them?

Norwegians are to be found scattered about in many places in the United States. One may meet a few Norwegians in New York, Rochester, Detroit, Chicago, Philadelphia, and New Orleans, yet I know of only four or five places where several Norwegians have settled together.45 The first company of Norwegian immigrants, as I have already said, settled in (1) Murray Town, Orleans County, New York State, in 1825. Only two or three families remain there now; the others have moved farther into the country, where they have settled in (2) La Salle County, Illinois State, by the Fox River, about one and one-half Norwegian miles northeast from the city of Ottawa, and eleven or twelve miles west of Chicago. From sixteen to twenty families of Norwegians live there. The colony was established in 1834.46 Another settlement is in (3) White County, Indiana State, about ten Norwegian miles south of Lake Michigan, on the Tippecanoe River. There are living in this place as yet only two Norwegians from Drammen, who together own upwards of eleven hundred acres of land; but in the vicinity good land still remains unoccupied.47 A number of Norwegians from Stavanger settled in (4) Shelby County, Missouri State, in the spring of 1837. I do not know how many families live there.48 A large number of those who came over last summer settled in (5) Iroquois County, Illinois State, on the Beaver and Iroquois rivers. This colony now consists of eleven or twelve families.

Usually the Norwegians prefer to seek a place where they can expect to find countrymen; but it is always difficult to get good unoccupied land in the vicinity of those who immigrated one or two years earlier.

6. What is the nature of the land where the Norwegians have settled? What does good land cost? What are the prices of cattle and of provisions? How high are wages?

In the western states, where all the Norwegian immigrants now go, the land is very flat and low. I had imagined that thick woods would cover that part of the land which had not yet begun to be cleared; but I found it quite different. One can go two or three miles over natural meadows, which are overgrown with the most luxuriant grass, without finding a single tree. These natural meadows are called prairies. From earliest spring until latest fall they are covered with the most diverse flowers. Every month they put on a new garb. The most of these plants and species of grass are unknown in Norway, or are found only here and there in the gardens of distinguished people. The prairies are a great boon to the settlers. It costs them nothing to pasture their cattle and to gather fodder for the winter. In less than two days a capable laborer can cut and rake enough fodder for one cow. Still the prairie grass is not considered so good as tame hay of timothy and clover. The soil on the prairies is usually rich, and free from stones and roots. In order to break a field, therefore, only a strong plow and four or five yoke of oxen are needed; with these a man can plough up one or two acres of prairie a day. Without being manured, the soil produces corn, wheat, buckwheat, oats, potatoes, turnips, carrots, melons, and other things, that make up the produce of the land. Corn is considered the most profitable crop, and yields from twelve to twenty-four barrels an acre. Oats and a large part of the corn are fed only to horses and cattle. As food for people wheat flour is most used. Barley and rye grow well in some places, and thrive; but I have not yet seen any of these grains. Barley, like oats, is used only for fodder. Beer is not to be found, and most of the milk is given to calves and hogs. For breakfast and supper coffee or tea is always served, but at other times only cold water is drunk. According to the price of beer in Chicago, a barrel would cost about twenty dollars.

It costs nothing to keep hogs in this country. They forage for themselves both in winter and summer, though they must be fed enough to prevent them, from becoming wild. This often happens, however, so that in many places whole droves of wild swine may be seen, which are hunted just like other wild animals. Since it costs so little to keep swine, it is not infrequent that one man has from fifty to a hundred. For that reason, also, pork is eaten at almost every meal.

It is natural that a country which is so sparsely populated should have a great abundance of wild animals. The Indians, who were the former inhabitants, lived entirely by hunting. If a settler is furnished with a good rifle and knows how to use it, he does not have to buy meat the first two years.49 A good rifle costs from fifteen to twenty dollars. The chief wild animals are deer, prairie chickens, turkeys, ducks, and wild geese. Wild bees are also found. The rivers abound with fish and turtles.

Illinois and the other western states are well adapted for fruit culture. Apple trees bear fruit in the fifth or sixth year after they are planted from the seed, and the peach tree as early as the second or third year. It is a good rule to make plans in the very first year for the planting of a fruit garden. Young apple trees cost from three to six cents apiece. Of wild fruit trees I shall name only the dwarfed hazel, which is seldom higher than a man, and the black raspberry, which is found everywhere in abundance. Illinois lacks sufficient forests for its extensive prairies. The grass on the prairies burns up every year, and thereby hinders the growth of young trees. Prolific woods are found only along the rivers. Most of the timber is oak; though in some places there are also found ash, elm, walnut, linden, poplar, maple, and so forth. The most difficult problem is to find trees enough for fencing material. In many places, therefore, they have begun to inclose their fields with ditches and walls of sod, as well as by planting black locust trees, which grow very rapidly and increase greatly by ground shoots. Norwegian immigrants ought to take with them some seed of the Norwegian birch and fir. For the latter there is plenty of sandy and poor soil in certain places. Indiana and Missouri are better supplied with forests than Illinois.

In many places in these states hard coal and salt springs are to be found. On the border between Illinois and Wisconsin territories there are a great many lead mines which belong to the government. Whatever else is found of minerals belongs solely to the owner of the ground. Illinois is well supplied with good spring water, something which Missouri to some extent lacks.

The summer in Illinois is much warmer than in Norway. On some days the heat in Norway may be just as intense as it ever is in Illinois or Missouri; but in these states the weather is clearer and brighter. It very seldom rains for a whole day until the end of summer; but when it does rain the downpour is violent and usually accompanied by thunder and lightning. The winter lasts from November until the end of March, at which time the ground usually begins to grow green. February is the coldest month. I have heard many Norwegians declare that they have never felt the cold worse in Norway than in America. Nevertheless, the cattle are generally kept out of doors during the whole winter, and the houses of Americans are not much better than a barn in Norway.

The price of government land has hitherto been $1.25 an acre, whether the land has been of the best kind or of poorer quality. The price is now going to be lowered and the land divided into three classes according to quality, and the prices will be regulated accordingly. Thus, I have heard that for land exclusively of the third class, half a dollar an acre will be asked.50

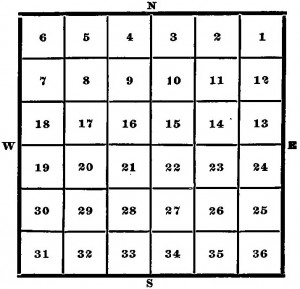

An acre of land measures about one hundred and four ells on each side.51 Forty acres, which is the smallest portion that can be bought from the government, is six hundred and sixty ells on each side. A tract of eighty acres is thirteen hundred and twenty ells north and south and six hundred and sixty ells east and west. If one buys two eighty-acre tracts side by side, one has one hundred and sixty acres in a square, and hence thirteen hundred and twenty ells on each side. With the smallest tracts the marks that are set by the government must be followed; but one is permitted to buy, for example, two eighty-acre tracts adjoining each other north and south, or even some distance apart from each other. An American mile is two thousand six hundred and forty ells in length. A section is a square which is a mile on each side and which contains eight eighty-acre tracts. A town or a township comprises thirty-six sections which are arranged as shown in the following figure.

The sixteenth section in each township is always school land and is the common property of the township. When, therefore, a township has attained a certain number of settlers, they can determine by a majority vote the manner in which the school land shall be used.52

It can be seen from the figure that a township measures six miles on each side. The location of a town or township is determined by two numbers, one indicating range and the other, township. That is, one begins to measure from a point toward north or south, and from another toward east or west. For every sixth mile toward north or south there is a new township, and for every sixth mile east or west, a new range.

Where the land has been surveyed by the government, marks and numbers for range, township, and section are found in the corners of all the sections. When one has found these marks for the piece of land which he wishes to buy, he goes to the land office, states which piece he wishes to have in the section named, pays the price set by the government, and receives without special payment his certificate or deed of conveyance.

The deed is very simple, as will be seen by the following copy:

Office of the Receiver, Danville, Illinois

January 6, 1838

No. 7885

Received of Ingbrigt Nielson Bredvig of Iroquois County, Illinois, the sum of fifty dollars as full payment for N. W. h. W. quarter of section number 14 in township number 27 north of range number 13 west comprising forty acres at $1.25 an acre.

$50.00

Samuel McRoberts,53

Receiver

When land is purchased from a private individual, who has himself bought earlier from the government, the price will be from two to thirty dollars an acre. Many swindlers are engaged in selling land which they do not own, whereby many strangers have been cheated. The surest and cheapest way is to buy from the government and curtly dismiss all speculators who, like beasts of prey, lie in wait for the stranger.

The government offers for sale every year only certain tracts. A person can nevertheless cultivate and settle upon land which has not yet been placed on the market, for such an one has the first right to buy it, when it is put up for sale.54 A piece of land acquired in this way is called a claim. To buy a claim is, therefore, to secure the right to buy the land from the government. Hence a claim is not yet one’s property. There are many speculators who enrich themselves by taking up claims and then selling their claim rights.

The prices of cattle and of the necessities of life vary most widely. At Beaver Creek a fairly good horse costs from fifty to one hundred dollars; a yoke of good working oxen from fifty to eighty dollars; a lumber wagon from sixty to eighty dollars; a milk cow with calf from sixteen to twenty dollars; a sheep two or three dollars; an average-sized pig from six to ten dollars; pork from six to ten cents a pound; butter from twelve to twenty-four cents a pound; a barrel of the finest wheat flour from eight to ten dollars; a barrel of corn meal from two and one-half to three dollars; a barrel of potatoes one dollar; a pound of coffee twenty cents; a barrel of salt five dollars. In Wisconsin Territory the prices of everything are two or three times higher. Ten Norwegian miles south of us and in Missouri the prices of most things are lower.

Wages are also very different in different places, and correspond closely with the prices of other commodities. In this vicinity a capable workman can earn from one-half to one dollar a day in winter, and almost twice as much in summer. Yearly wages are from one hundred and fifty to two hundred dollars. A servant girl gets from one to two dollars a week, and has no outside work except to milk the cows. In Wisconsin Territory daily wages are from three to five dollars; in New Orleans and Texas wages are also very high, but in Missouri, again, they are lower. At Beaver Creek we can now get men to break prairie for us at two dollars an acre, provided that we furnish board.55 For fencing ten acres with the simplest kind of fencing we figure on two thousand rails. In an average woods a good workman can split a hundred or a hundred and fifty rails a day. From one-half to one dollar is charged for splitting a hundred rails. Four thousand rails are required to fence in forty acres; and for one hundred and sixty acres eight thousand rails are needed, all figuring being based upon the simplest kind of fence.

7. What kind of religion is to be found in America? Is there any kind of order or government in the land, or can every one do as he pleases?

Among the common people in Norway it was a general belief that pure heathenism prevails in America, or, still worse, that there is no religion. This is not the case. Every one can believe as he wishes, and worship God in the manner which he believes to be right, but he must not persecute any one for holding another faith. The government takes it for granted that a compulsory belief is no belief at all, and that it will be best shown who has religion or who has not if there is complete religious liberty.

The Christian religion is the prevailing one in America; but on account of the self-conceit and opinionativeness of the teachers of religion in minor matters, there are a great many sects, which agree, however, in the main points.56 Thus, one hears of Catholics, Protestants, Lutherans, Calvinists, Presbyterians, Baptists, Quakers, Methodists, and many others. There are also various sects among the Norwegians, but they do not as yet have ministers and churches. Every man who is somewhat earnest in his belief holds devotional exercises in his own home, or else together with his neighbors.

I have already said that the United States has no king. Nevertheless, there is always a man who exercises just about as much authority as a king. This man is chosen for a term of only four years, and is called president. In matters which concern all the United States as a whole, the legislative power is vested in Congress, which is composed of men who are elected by the various states. Each of the separate states has its own government, just as Norway and Sweden have, but their common Congress, their common language and financial system unite them more closely. The number of the – states in the Union is at present twenty-seven.

For the comfort of the faint-hearted I can, therefore, declare with truth that in America, as in Norway, there are laws, government, and authorities. But everything is designed to maintain the natural freedom and equality of men. In regard to the former, every one is free to engage in whatever honorable occupation he wishes,57 and to go wherever he wishes without having to produce a passport, and without being detained by customs officials. Only the real criminal is threatened with punishment by the law.

In writings, the sole purpose of which seems to be to find something in America which can be criticized, I have read that the American is faithless, deceitful, and so forth. I will not deny that such folk are to be found in America, as well as in other places, and that the stranger can never be too careful; but it has been my experience that the American as a general rule is easier to get along with than the Norwegian, more accommodating, more obliging, more reliable in all things. The oldest Norwegian immigrants have assured me of the same thing. Since it is so easy to support oneself in an honorable way, thieving and burglary are almost unknown.

An ugly contrast to this freedom and equality which justly constitute the pride of the Americans is the infamous slave traffic, which is tolerated and still flourishes in the southern states. In these states is found a race of black people, with wooly hair on their heads, who are called negroes, and who are brought here from Africa, which is their native country; these poor beings are bought and sold just as other property, and are driven to work with a whip or scourge like horses or oxen. If a master whips his slave to death or shoots him dead in a rage, he is not looked upon as a murderer. The children born of a negress are slaves from birth, even if their father is a white man. The slave trade is still permitted in Missouri; but it is strictly forbidden and despised in Indiana, Illinois, and Wisconsin Territory. The northern states try in every Congress to get the slave trade abolished in the southern states; but as the latter always oppose these efforts, and appeal to their right to settle their internal affairs themselves, there will in all likelihood come either a separation between the northern and southern states, or else bloody civil disputes.58

The taxes in America are very low. I have heard of only two kinds of taxes here; namely, land tax and property tax. No land tax is paid during the first five years after land has been bought from the government. The property tax amounts to half a dollar on every hundred one owns in money or in chattels. Every man over twenty-one years owes the state four days of road work yearly.

In the event of war every man is bound in duty to bear arms for his country. In times of peace there is freedom from military service.

8. What provisions are made for the education of children, and for the care of poor people?

It has already been pointed out that the sixteenth section in every township is reserved as school land, and that the inhabitants of the township can themselves determine its use. Public education, indeed, is within the reach of all, just as any other thing; but it by no means follows that there is, therefore, indifference in regard to the education of the children. The American realizes very well what an advantage the educated man has over the ignorant, and he spares nothing in the instruction and education of his children. Nevertheless, I have met some elderly men who could neither read nor write. Two schools have now been started among the Norwegians at Fox River, where the children learn English; but the Norwegian language seems to be destined to die out with the parents. At least, the children do not learn to read Norwegian. At Beaver Creek no school is yet established, but most of the children who are old enough are taken into American homes, where their instruction is usually well cared for.59

In this state I have not yet seen a beggar. The able-bodied man is in no danger of poverty or need. By an excellent system of poor relief care is taken of those who are really needy. If a widow is left in straitened circumstances, the children are not taken away from the mother and made parish paupers as in Norway; but generous help is given to the mother for the support of both herself and her children, and for the schooling of the latter.60

9. What language is spoken in America? Is it difficult to learn?

Since so many people stream into the United States from the European countries, one must expect to find just as many different languages in use. But the English language predominates everywhere. Ignorance of the language is, to be sure, a handicap for Norwegian immigrants. It is felt especially on the trip to the interior of the country, if there is no one in the party who understands English. But by daily association with Americans one will learn enough in two or three months to get along well. Some half-grown children who came over last summer already speak very good English. Before having learned the language fairly well, one must not expect to receive so large daily or yearly wages as the native-born Americans.

10. Is there considerable danger from disease in America? Is there reason to fear wild animals and the Indians?

I shall not conceal the fact that the unaccustomed climate usually causes some kind of sickness among new settlers during the first year. Diarrhoea, or the ague, afflicts almost every one; but if a regular diet is observed, these sicknesses are seldom dangerous, and Nature helps herself best without medicine. The ague seldom returns unless one has attempted to drive it away by quack medical treatment.

There are no dangerous beasts of prey in this part of the country. The prairie wolf is not larger than a fox; but still it is harmful to the extent that it often destroys pigs, lambs, and chickens. Snakes are numerous, but small; and few of them are poisonous.61 The most poisonous kind is the rattlesnake; but even that is not nearly so venomous as many in Norway believe. I know two instances of persons being bitten by rattlesnakes, and in both cases the patients were cured by simple household remedies. Everywhere that the rattlesnake is to be found, a kind of grass grows which is usually regarded as the best antidote for its bite. One of the earliest Norwegians here has told me that he was once bitten by a rattlesnake, and that he found the application of dry camphor to be the most efficacious remedy for relieving the swelling.

The Indians have now been transported away from this part of the country far to the west. Nowhere in Illinois is there any longer danger from assault by them. Besides, these people are very good-natured, and never begin hostilities when they are not affronted. They never harm the Quakers, whom they call Father Penn’s children.62

11. For what kind of people is it advisable to emigrate to America, and for whom is it not advisable?-—Caution against unreasonable expectations.

From all that I have experienced so far, the industrious Norwegian peasant or mechanic, as well as the good tradesman, can soon earn enough here to provide sufficient means for a livelihood. I have already spoken of the price of government land, and I shall merely add that I know several bachelors who have saved two hundred dollars clear within a year’s time by ordinary labor. Blacksmiths are everywhere in demand. A smith who understands his trade can feel assured that his neighbors, in whatever place he settles, will help him build his house and smithy, and will even lend him enough money to furnish himself with bellows and tools. Two dollars or more is charged here for shoeing a horse; a dollar for an iron wedge; a dollar for a hay fork; and so forth. Competent tailors can also command a steady and good income, and likewise the shoemaker; but the latter will have to learn his trade anew, for here the soles of the shoes are pegged instead of being sewed. Turners, carpenters, and wagon-makers can also make a good living from’ their trades. An itinerant trader who is quick and of good habits can become a rich man within a short time, but he must not be afraid to undergo hardships and to camp outdoors night after night. Servant girls can easily secure work, and find good places. Women are respected and honored far more than is the case among common people in Norway. So far as I know, only two or three Norwegian girls have been married to Americans, and I do not believe that they have made particularly good matches. But there are many Norwegian bachelors who would prefer to marry Norwegian girls if they could.

Those desiring to emigrate to America should also carefully consider whether they have sufficient means to pay their expenses. I would not advise any one to go who, when he lands upon American soil, does not have at least several dollars in his possession. I believe that young people who have enough to pay their passage from New York to Rochester are in a position to emigrate. That will require about four or five dollars. Those who have large families should have enough left to pay their way directly to Illinois, where land is cheap and where plenty of work can be secured at high wages. Expenses for each adult from Norway to Illinois must be figured at about sixty dollars, in addition to expenses for board across the sea. On Norwegian ships the cost of the passage is just as much for children as for adults. It can be estimated, therefore, that forty-five dollars in all will be spent for children between two and twelve years old, and thirty dollars for children under two years.63 Those who do not have enough to pay their way can hire out to some one who is in better circumstances, and pledge themselves to work for him, for example, three years for fifty dollars a year. This will be to the mutual advantage of both parties. He who thus proposes to pay the traveling expenses of others must see to it that hev does not pay out so much as to be embarrassed himself, and that he does not take with him bad or incapable people. An employee who has come to America through such an arrangement ought to compare his pay and prospects here with what he had in Norway, and thereby be induced to fulfill the engagement upon which he has entered, for he is held by no other bond than that of his own integrity.64

People whom I do not advise to go to America are (1) drunkards, who will be detested, and will soon perish miserably; 65 (2) those who neither can work nor have sufficient money to carry on a business, for which purpose, however, an individual does not need more than four or five hundred dollars. Of the professional classes doctors and druggists are most likely to’ find employment; but I do not advise even such persons to go unless they understand at least how to use oxen, or have learned a trade, for example, that of a tailor.

Many go to America with such unreasonable expectations and ideas that they necessarily must find themselves disappointed. The first stumbling block, ignorance of the language, is enough to- dishearten many at once. The person who neither can nor will work must never expect that riches and luxurious living will be open to him. No, in America one gets nothing without work; but it is true that by work one can expect some day to achieve better circumstances. Many of the newcomers have been shocked by the wretched huts which are the first dwellings of the settlers; but those good people should consider that when they move into an uncultivated land they can not find houses ready for them. Before the land has been put into such shape that it can support a man, it is hardly wise to put money into costly living-houses.

12. What particular dangers is one likely to encounter on the ocean? Is it true that those who are brought to America are sold as slaves?

Many regard the trip across the ocean as so terribly dangerous that this one apprehension alone is enough to confine them forever to their native country. Of course, solid ground is safer than the sea; but people commonly imagine the dangers to be greater than they are. So far as I know, no ship with Norwegian emigrants for America has yet been wrecked. Even with a good ship, an able captain, and capable, orderly, and careful seamen, the passenger has to trust in the Lord. He can guide you securely across the stormy sea, and He can find you in your safe home, whenever His hour has come!

Two things about the sea voyage are very disagreeable; namely, seasickness and tediousness. I do not think there is any unfailing remedy for seasickness, but it is not a fatal illness. Small children suffer the least from it; women, especially middle-aged wives, often suffer considerably. The only alleviating remedy I know of is a good supply of a variety of food. I have noted particularly that barley gruel flavored with wine is frequently strengthening and helpful. It is well to prepare against tediousness by taking along good books, and something with which to occupy oneself. For this purpose I advise taking along harpoons and other fishing tackle as well.

A silly rumor was believed by many in Norway; namely, that those who wished to emigrate to America were taken to Turkey and sold as slaves.66 This rumor is absolutely ground less. It is true, however, that many who have not been able themselves to pay for their passage, have come only in this way: they have sold themselves or their service for a certain number of years to some man here in this country. Many are said thereby to have fallen into bad hands, and to have been treated no better than slaves. No Norwegian, so far as I know, has fallen into such circumstances,* nor is that to be feared if one crosses by Norwegian ships, and with his own countrymen.67

*All Norwegians who have been in America for a considerable length of time and who have been respectable and industrious, have fared well. Many have come over by an arrangement whereby other Norwegians have paid for them, but have nevertheless been fully as much their own masters. After a short time they have usually worked out their debt.— Rynning.

13. Guiding advice for those who wish to go to America.

When persons wish to emigrate to America singly, they can not expect to chance upon opportunity for sailing directly from Norway, inasmuch as this country has no commerce with the United States. They must go, therefore, either to Gothenburg,* Sweden, Bremen, Germany, or Havre, France. From all these places there is frequent opportunity to secure passage to the United States, and the fare is usually less than from Norway. But when several wish to emigrate at the same time, I should rather advise them to go on Norwegian ships and with Norwegian seamen, because they will feel safer. For the same reason it is also best to go with a captain who has previously been in America; for example, Captain Behrens of Bergen, whom I can recommend as an able man, or one of the captains who have conveyed passengers from Stavanger to New York.

* Some bachelors from Numedal went last summer from Gothenburg to Newport, Rhode Island. They spent only thirty-two days in crossing the ocean, and praise their Captain Ronneberg highly.—Rynning.

These immigrants were the Nattestad brothers and their companions, the account of whose voyage is given by Ole Nattestad in his Beskrivelse, 11.

When several wish to emigrate together, they must apply to a broker in ,the nearest seaport, who will help them to bargain for the cheapest fare. They must investigate carefully whether the ship is a good sailing vessel and in good condition. With reference to the bargain it may be remarked that the fare on Norwegian ships has hitherto been thirty dollars, for children as well as adults. From the ports of other countries the fare for adults is generally less, sometimes only twenty dollars; and for children under twelve years either half of that or nothing.

The charter, or the written contract, ought to be as precise and detailed as possible. It ought to be written both in English and Norwegian. I shall name some particular provisions that ought not to be omitted: (a) The captain (or the owners) are to supply wood and water for twelve weeks. The water is to be provided in good casks, so that it will not spoil, and three quarts are to be measured out to each passenger daily. If the water in some casks is spoiled, the good water is to be used up before beginning with the bad, and the captain shall take water for his own use from the same barrel as the passengers, (b) The passengers, indeed, must supply themselves with provisions, but the captain shall see to it that every one takes with him sufficient provisions for twelve weeks. The passengers must also furnish their own light, (c) For the sum agreed upon the captain shall land the passengers at the destination determined upon without any additional expense to them,* either under the name of landing money, quarantine money, corporation money, gratuities, or the like, (d) The fare is to be paid in advance and a receipt given which is written both in English and Norwegian. If the captain on his own risk takes along any one who has not paid in full the sum agreed upon, then he has no further right to demand more as soon as he has taken the passenger and his baggage aboard. (The last provision is a safeguard against having the captain take aboard any one who, on account of his poverty, will either become a burden to the rest or else be given up to the arbitrariness of the captain.)

*This provision is very necessary; for otherwise an unscrupulous captain, under one pretext or another, might demand an additional sum from his passengers and, by virtue of his authority and because of their ignorance and unfamiliarity with the language, might force them to pay it.—Rynning.

I should advise every one who goes to America to exchange his money for silver and gold, and not take a draft. Spanish piasters are worth as much as American dollars, but five French francs are six cents less. In an American dollar there are one hundred cents, and each cent is equivalent to a Norwegian shilling. There are twelve pence or twelve and one- half cents in a shilling. In America there are silver coins which are worth one half, one fourth, one eighth, one tenth, one sixteenth, and one twentieth of a dollar. The smallest coin current in Illinois equals six and one-fourth cents. All kinds of silver or gold coins are accepted in America; Norwegian silver coins, indeed, that are less than half a dollar, are disposed of with considerable profit.

The best time to leave Norway is so early in the spring as to be able to reach the place of settlement by midsummer or shortly after that time. In that way something can be raised even the first year; namely, buckwheat, which is planted in the last days of June; turnips, which are planted in the latter part of July; and potatoes. It is very unfortunate to go too late in the year to gather fodder for one or two cows, and build a house for the winter.

Hitherto the Norwegian immigrants have always sought passage to New York. From there to Chicago the least expensive way is to go by steamer up the Hudson River to Albany; from Albany to Buffalo by canal boat, which is drawn by horses; from Buffalo by steamer over Lakes Erie, St. Qair, Huron, and Michigan, to Chicago. From here the route goes by land, either south to Beaver Creek, or west to Fox River. From New York to Buffalo one can get transportation for from three to four dollars with baggage, and from Buffalo to Chicago for from nine to twelve dollars. From Chicago to Beaver Creek drivers from Wabash usually ask one dollar for every hundred pounds. Every contract with the steamboat companies or drivers should be written, and with the greatest particularity, if one does not wish to be cheated. To be on the safe side one should figure that it will take about thirty dollars for every adult from New York to Beaver Creek or Fox River. For children between two and twelve years of age half of that is always paid, and nothing for children under two years or who are still carried in arms. The route mentioned from New York to Beaver Creek I compute to be about two hundred and fifty Norwegian miles.

One of our party who arrived last fall did not take the steamboat from Buffalo any farther than to Toledo on Lake Erie. Here he bought a horse and wagon, and conveyed his luggage to Beaver Creek himself. In this way he and his family traveled to their destination somewhat cheaply, but they were also a good deal longer on the way than those who took the steamboat.

For those who wish to go to Missouri,* unquestionably the quickest and cheapest route is by way of New Orleans. But it must be noted in this connection (1) that one can seldom go to New Orleans except in ships which are sheathed with copper, and (2) that New Orleans is very unhealthful and insalubrious, except from the beginning of December until April. But this is the worst time of the year to be without houses—which is the usual fate of settlers.

* According to the assurance of Kleng Peerson, who knows the country best, and who from the beginning has been the guide of the Norwegians, Missouri is the state where it is now most advisable for immigrants to go. They must then go first to St. Louis on the Mississippi, from there to Marion City, and from there to “the Norwegian settlement on North River, Shelby County.”—Rynning.